September 14, 2017 report

Code for fine-tuning elastomers to mimic biological materials

(糖心视频)鈥擝iological material such as bone and muscle tend to have a wide range of elasticity and rigidity that is different from synthetic materials. In general, with synthetic materials, as stiffness increases, elasticity decreases. Biological materials, on the other hand, do not exhibit such a direct relationship. There is much interest in finding materials that mimic biological materials for use as prosthetics and other functions. One such material is the bottlebrush polymer.

Researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Akron, and Carnegie Mellon University sought to outline the available stiffness and extensibility with bottlebrush polymers and suggest a general strategy for fine-tuning three characteristics of the bottlebrush polymer to mimic the mechanical properties of biological tissues. Their letter can be found Nature.

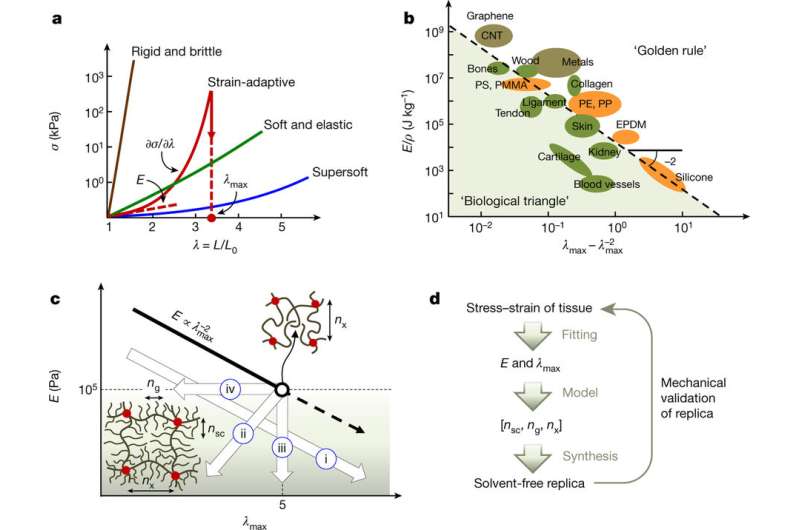

Synthetic elastomers tend to follow the "golden rule" of material objects. As the stiffness of the material increases (E), its extensibility (or maximum elongation, 位max) decreases. The range of possible E and 位max is mainly defined by the chemical composition of the polymer backbone.

Biological materials do no obey this "golden rule." They inhabit what the authors call the "biological triangle" of E and 位max combinations that are currently inaccessible for synthetic materials. Furthermore, the available E and 位max do not obey a strictly inverse relationship. Brush polymers have been found to have stiffness and flexibility more similar to biological systems. Additionally, comb polymers and triblock copolymers can be employed to adjust the polymer architecture.

Through crosslinking, bottlebrush macromolecules can produce a solvent-free polymer network. In other words, they are elastomers that readily respond to an electrostatic field by changing shape. Previous work by this group identified and synthesized this special kind of elastomer. Unlike other types of electrostatic polymers, bottlebrush elastomers respond to a relatively small electric field and do not require pre-straining.

A key property of bottlebrush elastomers is their stiffness and extensibility, E and 位max, are independently controlled by three architectural parameters: the degree of polymerization of the side chains (nsc), the spacer between neighboring side chains (ng), and the backbone strand (nx). Typical linear chain elastomers are "one-dimensional," relying on one parameter鈥攖he backbone strand, nx鈥攁s the way to manipulate E and 位max.

In order to test how to manipulate these three properties to access combinations of E and 位max within the "biological triangle," the authors used various PDMS elastomers as model systems. They began by measuring the stress-strain curves for a broad range of elastomers to corroborate theoretical predictions.

After testing several model systems, the authors then identified correlations between nsc, ng, and nx and the elastomer's mechanical properties. They found that there were four distinct correlations between E and 位max for several combinations of nsc, ng, and nx: 1) E decreases as 位max increases (the typical relationship seen in synthetic polymers), 2) a concurrent decrease in E and 位max, 3) E varies while 位max stays constant, and 4) 位max varies while E stays constant.

Finally, taking these correlations, the authors then devised rules for choosing the right combination of nsc, ng, and nx to mimic the stress-strain curves for certain biological systems. They did this by relating a known mathematical relationship between the equilibrium stress and network elongation to the elastomer Young modulus and strain-stiffening parameter. These are then related to nsc, ng, and nx to provide a code for choosing the right combination for a particular E and 位max pair.

By manipulating these three properties, Vatankha-Varnosfaderani et al. were able to match the elastomer's stress-strain curve to that of representative biological materials. They successfully found the combination to mimic jelly fish tissue. However, adaptive biological materials, such as lung, muscle, and artery tissue, revealed synthetically prohibitive nsc, ng, nx triplets. To overcome this, they used triblock copolymers with varying lengths of bottlebrush middle block. From these architectures they were able to obtain polymer materials that had the appropriate triplets to mimic biological stress-strain curves.

This research has implications for producing synthetic materials that are beyond the narrow range of stiffness and elasticity available to linear polymers. Future research may include fine-tuning the chemical composition of the elastomers for specific needs such as biological compatibility, conductivity, or solubility.

More information: Mohammad Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani et al. Mimicking biological stress鈥搒train behaviour with synthetic elastomers, Nature (2017).

Abstract

Despite the versatility of synthetic chemistry, certain combinations of mechanical softness, strength, and toughness can be difficult to achieve in a single material. These combinations are, however, commonplace in biological tissues, and are therefore needed for applications such as medical implants, tissue engineering, soft robotics, and wearable electronics. Present materials synthesis strategies are predominantly Edisonian, involving the empirical mixing of assorted monomers, crosslinking schemes, and occluded swelling agents, but this approach yields limited property control. Here we present a general strategy for mimicking the mechanical behaviour of biological materials by precisely encoding their stress鈥搒train curves in solvent-free brush- and comb-like polymer networks (elastomers). The code consists of three independent architectural parameters鈥攏etwork strand length, side-chain length and grafting density. Using prototypical poly(dimethylsiloxane) elastomers, we illustrate how this parametric triplet enables the replication of the strain-stiffening characteristics of jellyfish, lung, and arterial tissues.

Journal information: Nature

漏 2017 糖心视频