Proposed federal abortion ban evokes 19th-century law so unpopular it triggered the backlash that led to Roe

Sen. Lindsey Graham has proposed a barring the procedure after 15 weeks. This push to restrict abortion access across the country follows a rash of new state laws passed by Republicans after the in June.

If American history is any guide, these efforts will ultimately neither reduce abortions nor remain settled law.

I am a who has studied American culture and law in the wake of the 1873 Comstock Act—the first U.S. effort to restrict access to birth control and abortions. My research finds that previous state and federal efforts to regulate the sexual expression and reproduction of Americans led to unintended consequences—and, in the long term, these laws failed.

Already, I see signs that new anti-abortion laws are triggering a similarly undermining backlash.

How 'obscene'

In 1873, Congress hurriedly passed a law making it "obscenities" through the U.S. mail. The legislation was branded the Comstock Act after its most vigorous proponent: , a U.S. postal inspector and evangelical Christian who believed sexual activity was a sin unless it occurred between a married man and woman for the purpose of procreation.

Birth control and substances used to induce abortion were included in the definition of "obscenity," because Comstock and his supporters believed that life and death were God's decisions. The law also banned mailing erotic images and literature. In Comstock's expansive view, this category included .

State versions of the original Comstock Law soon swept the United States. By 1900, 42 states had passed outlawing the production, sale, possession or circulation of "obscene" matter in their own jurisdictions.

These statutes ruled until the Supreme Court declared a right to privacy in medical decision-making nearly 100 years later, in .

This is the same ruling that was cited eight years later to protect the right to have an abortion in the now defunct .

Impractical enforcement

Comstock zealously enforced the laws he'd advocated for, both as a detective for the privately funded New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, and as an inspector for the U.S. Post Office Department. In attempting to eradicate contraceptives—including condoms and early forms of diaphragms—Comstock organized the arrests of numerous defendants.

However, he had difficulty getting prosecutors, juries and judges to see the seriousness of many of the "crimes" he investigated. In the late 19th century, wealthier Americans already .

"Of all the indictments prior to 1878, pending in the Court of General Sessions, not one has been tried the past year," Comstock wrote in his 1879 annual report for the society.

In one of these cases, , Comstock was chastised by a New York City district attorney named Phelps for his "sharp practice" in investigating Dr. Sarah Blakeslee Chase. These included his posing as a client to obtain birth control products and repeatedly harassing the suspect. A grand jury threw out the case, stating that it "did not think it for the public good."

Even when Comstock obtained a conviction, many defendants were pardoned immediately.

Enforcing new anti-abortion laws is similarly unpopular with many legal professionals today. Shortly after the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Dobbs, vowed not to bring indictments in cases involving abortion.

As they recognize, conservative courts in jurisdictions with zealous anti-abortion prosecutors—who —will soon be filled with a host of extremely sympathetic defendants: relatives who assist in obtaining an illegal abortion, , and those who choose to help in making the best possible decisions for their health.

Enforcement of America's new Comstock laws will likely once again make witnesses and defendants more sympathetic in the eyes of judges and jurors—and the public—undermining whatever support remains for these laws.

Beyond prosecutions, the tactics necessary to prevent women from obtaining abortions are even less practical today than they were in the late 19th century.

Enforcing anti-abortion laws may include , and attempting to about sexual health. All of these would require laborious investigations and extensive cooperation from law enforcement agencies and private corporations who will likely have little desire to involve themselves in unpopular prosecutions.

And that's assuming that any of these methods survive court challenges.

Uniting disparate factions

By the time of Anthony Comstock's death in 1915, backlash to his zealous overreach had provoked among activists and attorneys determined to defeat his agenda.

Women's rights activists, including Margaret Sanger, Emma Goldman and Mary Ware Dennett—formerly focused on competing goals and strategies—joined in common cause to repeal the Comstock laws. Their efforts led to the creation of new and powerful national civil liberties organizations, including Planned Parenthood and the American Civil Liberties Union. Both used lobbying and lawsuits to contribute to the death of the original Comstock laws.

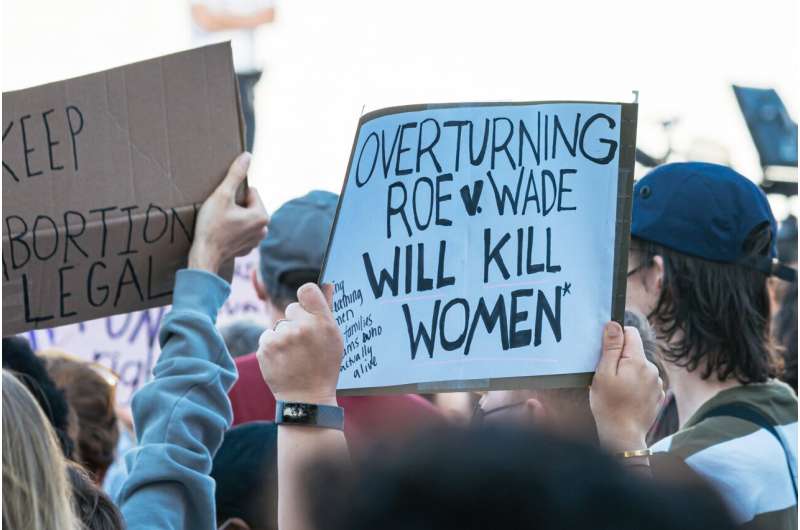

These groups are new abortion restrictions today. And once again, post-Dobbs, disparate individuals and groups are raising their voices in common cause.

from around the country have begun lobbying politicians and forming their own pro-choice political action committees for the first time. TikTok influencers like are rallying young citizens to vote for pro-choice politicians. And , from one-time provocateur Howard Stern to the hosts of the true crime show "My Favorite Murder," are sharing resources with their listeners and expressing support for abortion rights.

Ballot box backlash

and energized voters are turning out to support candidates and ballot initiatives that reflect the nation's .

. And more states will soon vote on state constitutional protections for abortion, .

The Comstock laws were not repealed quickly. And it's now clear that American women's right to reproductive health care remained tenuous after their demise.

Viewing the past as prolog, however, suggests that, once again, anti-abortion laws will cause unintended consequences that, in the long run, will render them both ineffective and ultimately futile.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()